Native American fighters in WWII Europe

New novel research: From liberating Dachau to creating unbreakable codes, Native Americans helped win the war in Europe. Plus fiction editing.

I’m often amazed by the things I find out while doing research for my novels. And as I work on a new book, I’m still discovering more about WWII that I hardly knew.

This new novel is the third book in my Wendell Lett series. It isn’t even set during WWII, yet the consequences of the war still loom large. Here’s the story (as of now):

In 1950, former WWII hero and combat deserter Lett has to go undercover to stop a possible Soviet mole at a secret UFO research site in a remote Pacific Northwest forest. He can’t trust anyone as he tries to figure out the real spy—and clear his own name.

The story takes place on the tribal land of the Yakama Nation, with a supporting character who’s Native American. While he knows about the violence and destruction that the white people inflicted on his own tribe and others, he’s also witnessed firsthand the extreme self-destruction that they committed against each other.

That’s because he fought in WWII, in the European Theater, all the way to the liberation of Dachau Concentration Camp. He might be fictional, but his experiences mirror those of many other Native Americans.

Native Americans join the fight

Native Americans volunteered in huge numbers during World War II despite growing up on reservations and facing poverty, limited education, broken treaties, and discrimination. About 44,000 total served in the armed forces, which is a lot given their population at the time.

Many people know about Native Americans’ contributions in the Pacific during WWII thanks to the 2002 movie Windtalkers, which tried to tell the story of the Navajo Code Talkers but focused too much on conventional war movie tropes and action—and on Nicholas Cage—at the expense of the Native American protagonists’ unique efforts.

But there’s been less attention paid to the critical roles Native Americans played in the European Theater, especially those of the 45th Infantry Division and the Comanche Code Talkers.

The Thunderbird Division in Europe

The 45th Infantry Division, also known as the “Thunderbird Division,” was named after a sacred symbol in many Indigenous cultures. About 2,000 Native American soldiers from different tribes across the country made up about one-fifth of the 45th. These men brought their unique perspectives and skills to some of the war’s most important battles. Three received the Medal of Honor: Jack Montgomery (Cherokee), Van T. Barfoot (Choctaw), and Ernest Childers (Muscogee [Creek]), the first Native American awarded the Medal of Honor in World War II.

The 45th Infantry saw plenty of tough duty in the European Theater, starting with the invasion of Sicily in 1943. They fought their way up Italy, survived the meat grinder in battles at Salerno and Anzio, and later helped liberate southern France during Operation Dragoon.

By 1945, the division had made it deep into Bavaria, the heart of Nazi Germany. They captured Nuremberg and Munich, two cities that were key to Hitler’s rise to power. But their most difficult job came on April 29, 1945, when they liberated Dachau Concentration Camp.

How’s this for irony? The Thunderbird Division’s patch was a swastika before the Nazis ripped off the ancient symbol. For Native American tribes, it had symbolized peaceful and sacred themes such as life, harmony, well-being, and spirituality.

The Liberation of Dachau

The 45th Infantry Division was one of the first Allied units to reach Dachau. The soldiers found scenes of unimaginable horror: emaciated prisoners, piles of corpses, clear evidence of mass executions. For many Native American soldiers, whose cultural values emphasized respect for the dead and the sacredness of life, the experience must’ve been especially devastating.

GI Bennett Freeny, a Chickasaw and Choctaw from Oklahoma, entered Dachau as a medic. Freeny was one of the first to care for the camp’s survivors, and he and his fellow soldiers worked hard to save the starving and seriously ill.

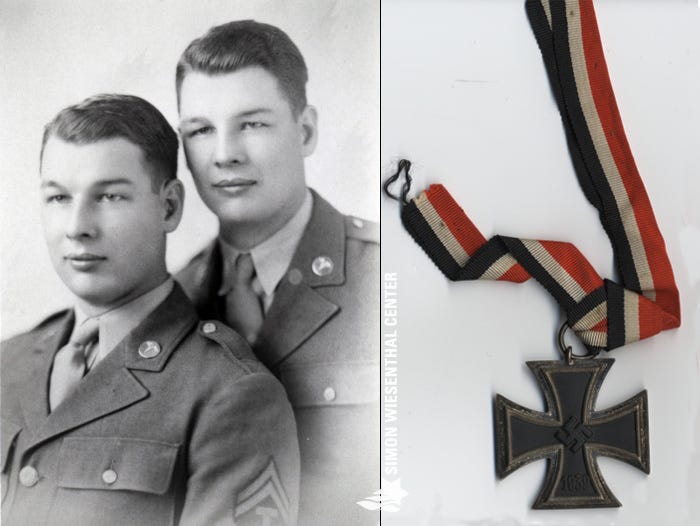

Fellow GI Ace Caldwell, who served with Freeny, once wrote to Bennett Freeny’s daughter about her father:

“… Bennett and I were both medics with the 45th and we encountered a great many prisoners who had contracted Typhoid and other ailments, and even more who had been starved … We were very disheartened by the condition of these poor souls and still enraged by the evil and carnage we had encountered liberating the camp.

“A German SS officer walked through as though still in command and eyed us arrogantly and with a sort of sneer. Your dad stood, walked up to him, and pulled out his knife. A couple of our boys stood by and prevented the officer from moving. Your father, one at a time, cut his medals and insignias off his uniform—Death Head, Edelweiss insignia, various patches and came to the Iron Cross hanging around his neck. Bennett grabbed it, cut the ribbon, and said, ‘This is the sign of a hero—there are no heroes here’ and stuffed all the medals and patches in his pocket. A few of the prisoners who were able, clapped.

“We were young men who had a lifetime of horror and violence visited upon us by age 23. None of us would ever be the same, but that day your father was bigger than life . . .”

Comanche Code Talkers in Europe

Along with Navajo Code Talkers in the Pacific, Comanche soldiers created their own secret code to confuse the Nazis in Europe—using languages that US authorities once forbade them to speak.

Fourteen Comanche Code Talkers served with the US Army, and 13 landed on the beaches of Normandy during the D-Day invasion. They used their language to send secret messages that German intelligence couldn’t figure out. The Comanche word for “turtle” meant tanks, for example, and “crazy white man” Adolf Hitler. Their code proved hugely important in big battles like the Battle of the Bulge and the push into Germany.

Charles Chibitty, a legendary Comanche Code Talker, was a passionate advocate for Native American contributions in World War II until his passing in 2005. He also made sure people knew that he and his fellow Code Talkers faced unique hurdles beyond the dangers of war. They had to repeatedly convince skeptical white officers that their language was even worth using.

Cultural Challenges and Triumphs

Sources say that Native American soldiers adapted remarkably well to military life, often outperforming their peers in endurance and marksmanship. Fighting for the white man brought cultural tensions and outright racism, too, yet Native American frontline warriors earned the respect of their fellow white soldiers through their bravery and skill.

And their spiritual beliefs kept them going. Some carried medicine bundles and took part in prayer rituals before battle, drawing strength from old traditions that emphasized harmony and resilience.

For decades, Native Americans’ contributions went largely unrecognized. But in recent years, their stories are being preserved and celebrated. You can learn more here:

National WWII Museum: Native Americans in WWII, Ernest Childers

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum: 45th Infantry Division

U.S. Army: Comanche Code Talkers

Charles Chibitty’s Biography: Wikipedia

Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian: Why We Serve

Simon Wiesenthal Center: 76 years ago: Dachau Concentration Camp Liberated

Looking for a fiction editor?

Finishing a novel draft is a big accomplishment—congratulations! But in many ways, it’s just the beginning. Most writers can benefit from the right guidance and thoughtful edits, and that’s where I can help.

I know what writers need to improve and engage readers by drawing on over 20 years’ experience as a published editor, author, and translator of fiction.

My specialties are historical, espionage, and psychological/crime thrillers, but I offer expertise for all types of stories, including creative nonfiction.

You can find out more on my website, or on the Reedsy platform, with plenty of testimonials.

Not sure what you need? Get in touch and ask me anything—you can simply reply to this email.

Find me on Bluesky

I’m on Bluesky now after ditching Twitter (X, sorry; not sorry), which I’d abandoned years ago, frankly. I’m enjoying it so far. Less anger, smarter posts—much like on Substack Notes. Find me at steveawriter.

My latest novels

Are you into Cold War espionage tales with exotic locales? Or maybe you like a psychological crime thriller with a twist? Check out Lines of Deception and Show Game.

And if you like them, or any of my novels, please give them a review or rating at your favorite online book retailer such as Amazon, Goodreads, Barnes & Noble, or other review-based sites.

Please also follow me on my Amazon Author page and Facebook Author page.

I hope the new year’s treating you well so far. Take care of yourselves.

Steve

Thanks so much, Karen, and for reading it.

Your post today reminded me of the movie "Wind Talker's" and further shows the outstanding contributions that our "Native American" brothers have given to the United States of America. Thank You, Terrific article today, and will reStack ASAP 💯👍🇺🇸